Doubles mean trouble

The influence of City of Glass and Possession

Eternal Gaze of the Sightless Void was a horror comic that channeled my anxieties about the pandemic and the resultant upending of the social contract.

Another of the themes I have been eager to explore in my writing is the concept of the double or doppelgänger. I can’t say how or when I became fascinated by the idea of a double. Maybe it’s because my mom is a twin? Perhaps some deep recess of my infant brain was deeply affected by seeing two of the same person, leaving an indelible curiosity. Maybe it’s because my brother and I are “Irish twins?” Meaning we were born so close together (he in late December, I in early January, nearly one year apart) that we appear ostensibly twinned.

The phrase, almost an accusation, “You two look exactly alike; are you twins? " has punctuated our lives, emphasizing our physical likeness over our individual identities.

Despite feeling unique and individual within, this external perception of me as a mere duplicate likely fueled my strange fascination with doppelgängers. Though I haven’t thought of the book in years, as I write this, I vividly recall reading Stephen King’s The Dark Half during a family vacation, a novel about a killer twin!

My awareness of this interest truly crystallized in college. Ever the seeker after arcane knowledge, I discovered that the literary figure W.B. Yeats was not just a poet but also dabbled in the occult. This led me to take a university course on Yeats, where I learned that while his involvement in occultism might not have been as extensive as I had imagined. Yeats was not, in fact encoding secret wisdom into his poems and plays.

In an aside with the professor, I mentioned Yeats’ connection with the Golden Dawn and occultism, and he laughed. He said that there was a time he would’ve thought it was absurd to think Yeats was into the occult, except he had a student once take a Yeats play and, side by side with a Golden Dawn ritual, show him how they were duplicative.

Yeats was not the occultist I wanted him to be, but I learned that he, too was fascinated with the idea of the double. Only Yeats’ concept of a double was the divine artistic self in contrast to the mortal author and the tension that arises between the two. In looking for wisdom, I found more doppelgängers.

The obsession resonated within me, leading me to purposefully seek stories about physical doubles or narratives that played with this concept. This exploration inspired me to write something of my own crafted around this theme.

So, for my next horror comic, I wanted to work with the idea of doubling. There are two works that handle the theme of doubles that very much served to inspire A Story We Tell Ourselves.

The first is City of Glass by Paul Auster.

Auster’s novel blends semiotics and epistemology to blur the lines between reality and fiction. This approach has profoundly influenced me, particularly in how it uses narrative structure to delve into existential questions.

City of Glass is a labyrinthine exploration of themes like the construction of meaning from life's inherent randomness and the role of language as a symbolic trap that both confines and defines us.

One of the most captivating aspects of City of Glass is the complex identity of its main character, Daniel Quinn. The novel asserts that "nothing is real except chance," a notion personified in Quinn. He is a writer who leads a vicarious existence through his detective character, Max Work, whose works are penned under a pseudonym. Quinn’s matryoshka-like sense of reality is further blurred when he is mistaken for a detective named Paul Auster, our real-life novelist.

As Quinn embarks on this detective journey, the boundaries between the real and the fictional start to dissolve. He transitions from being the story's protagonist to merely one element in a broader narrative, emphasizing one of the novel's themes, that we are all, in some way, characters in someone else's story—especially if we are fictional beings like Quinn.

City of Glass poses an exciting question: "To what extent would people tolerate blasphemies, lies, and nonsense if they gave them amusement?"

Drawing inspiration from City of Glass, in A Story We Tell Ourselves I wanted to explore the nature of identity through perception. How much are we a construct of the mind’s fiction and how much are we shaped by the chaos of reality? Is your story self-authored or merely a narrative written by unseen hands?

The other work to inspire A Story We Tell Ourselves is Possession (1981), directed by Andrzej Żuławski and starring Isabelle Adjani and Sam Neill. This wild film delves into the complexities of human relationships through a unique and surreal lens. It’s essentially about a couple going through a very intense and emotional breakup. Possession uses doubles differently from City of Glass, which explores constructed identity and how we relate to ourselves—Possession is more about how we relate to each other. Possession uses doubles to examine interpersonal dynamics.

In Possession, the concept of doubles is multifaceted, representing various aspects of the self and how these aspects interact within the confines of a relationship. The film portrays a couple’s tumultuous breakup, showcasing the intense emotional turmoil that accompanies the breaking of a deep bond.

The doubles here symbolize different facets: the persona one believes they portray, the true self that might be hidden or suppressed, the version of oneself that exists within the relationship, and the version of oneself as perceived by the partner.

This portrayal of doubles suggests a fragmentation of self that occurs within the context of a relationship. It's a study of how our multiple selves can sometimes clash or diverge, leading to misunderstandings, conflicts, and the eventual breakdown of the relationship. This fragmentation is not just about personal identity but also about how others perceive us—an intricate dance of understanding, misconception, and possession—challenging the viewer to confront the unsettling possibility that we might not fully know ourselves.

The doppelgänger theme, in this context, becomes a tool for dissecting the multifaceted nature of human relationships, the masks we wear, and the often stark differences between our perceived and actual selves.

By weaving together these themes, the story becomes more; it becomes a mirror reflecting the complexities of the human psyche and the convoluted web of relationships we navigate throughout our lives. It's a film that acknowledges the inherent contradictions and conflicts within ourselves and our interactions with others—the balance of self-discovery and the quixotic quest for understanding in the labyrinth of human emotions. It also bears a warning—to wade too deeply into the internal conflict is to treat with monsters. You’re gonna need to watch Possession to understand what that means.

In A Story We Tell Ourselves, I wanted to blend these influences—the introspective exploration of identity from City of Glass and the complex interplay of interpersonal dynamics from Possession. My aim was to create a narrative that entertains and hopefully prompts readers to reflect on their own identities and how they relate to others.

My use of doubles or doppelgängers in Story is much more metaphorical. There are no clones or twins in my tale. It’s a narrative that incorporates the idea of memory's infallibility and how much our memories shape who we are and who we become; the double I’m focusing on in Story is the double in ourselves. The secret self that inhabits us all.

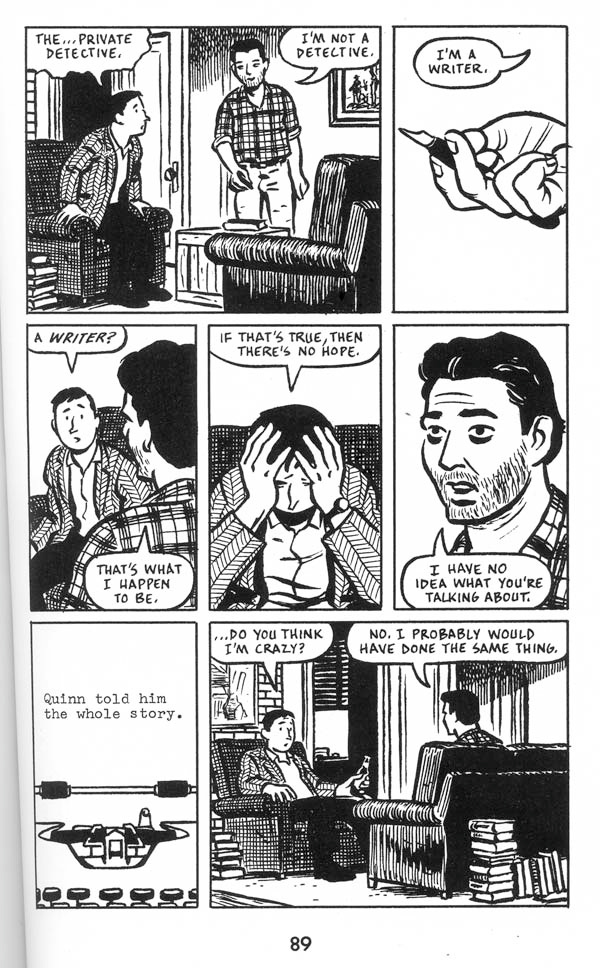

The above is a little peek into how Anna and I use panel layouts and reflections to show a woman with something to hide from herself in A Story We Tell Ourselves.

Everything Anna’s turning in for Story is phenomenal. I have a fair amount of dread that I didn’t quite nail it, but it soothes my nerves knowing at least Anna is killing it.

In the meantime, if you'd like to support the comic financially, you can pledge using the above button. You can pledge any amount that suits you, but Substack does set the minimum pledge at $5.

Once A Story We Tell Ourselves kicks off, likely this March or April, your pledge will automatically convert into a paid subscription at the frequency and amount you pledged. When the comic concludes, subscriptions will be turned off and you’ll no longer be charged.

Story should run for about five or six weeks, which might help you decide on your pledge level.

Regardless of whether anyone chooses to pledge or not, Story will be accessible to all. Any funds generated will be reinvested into paying artists for their invaluable contributions.

Whether through pledges or simply following along, your support allows me to continue creating. So, stay tuned for updates and the official launch of A Story We Tell Ourselves.

per somnium invenimus fatum nostrum

Oh man, I've been thinking about doubles a lot too! I'm dedicating all next month's writing to em.